“This is utterly spectacular!”

Tasting Note: “Slightly spicy nose. This is utterly spectacular! Glittering with acidity. So precise. So much fruit and yet not fruity. Peach, apricot and kumquat. Papaya. So much length and juice and angles and yet, also, swooping curves. There is both jubilance and tension in this wine. Generosity and fullness and yet chisel and etch. But it's still so young. I'd love to taste this in a year or two. (TC)” 17.5 points

buy online here

We arrived at Natte Valleij* in the pouring rain. The lavish tumbles of flowers growing unfettered around the beautiful, historic Cape Dutch farmhouse were dripping even faster than the rain was coming down. Dogs, an indeterminate pack of sizes, speeds and colours, undeterred by the weather, poured out of the house and across the mossy brick cobbles, barking a riotous welcome. Alex Milner came out and down the old stone steps, also undeterred by the rain plastering his impossibly straight, floppy, unbrushed hair across his eyes. Smiling, whippet slim in a pair of well-worn trousers with a small hole by the pocket and battered shoes, saying welcome. ‘Come!’ Bedraggled, we walked into a beautiful room with ancient wooden floors and antique furniture, where a log fire was crackling brightly in front of a cluster of comfy sofas – lit to warm us up on a cold, gloomy Cape winter’s day.

Tasting by the fire in the Natte Valleij drawing room

In 2022, I wrote about Milner, commenting that he is ‘not a winemaker with luxury in mind’. Having visited him at Natte Valleij in May this year, I now realise this is both ironical and somewhat of an understatement. The family farmstead is the epitome of unpretentious, unintended shabby chic, a sort of gently faded grandeur. It’s a place, I suspect, where the gardens (full of massive, gloriously old trees, masses of flowers) possibly receive more attention than the house. And it’s a place where the warmth of the welcome is clearly way higher up on the priority list than an exterior-walls paint job. It’s also, as I found out first-hand, a place where the most extraordinary wine is made in the most unprepossessing place.

The main entrance to Natte Valleij's Cape Dutch farmhouse

Ever since I first came across Milner and his wines back in 2014, I have been convinced that there is something very special about him. There is certainly something very special about his wines. As I wrote back in 2022, it was Milner’s wines that triggered my Cinsault revelation – a seismic shift in how I understood the variety and its extraordinary potential for purity and translucent beauty as a varietal wine. It was the first time I confronted the Cinsault conundrum: how is it possible that this humble ‘blending’ grape grown in hot climates from dry-farmed vines is capable of producing such low-alcohol, ethereal wines that are also, paradoxically, loaded with intensity?

Milner himself is a conundrum. He is the grandson of a famous English racehorse owner and breeder, Sir George Edward Mordaunt Milner, 9th Baronet (also an author of five books), who bought Natte Valleij in 1969. Natte Valleij, in Stellenbosch, had been originally established as a wine farm in 1715 and is one of the oldest wineries in South Africa. But wine production had come to a halt a couple of decades before Sir Mordaunt Milner bought it, and it was very run-down. They poured money into converting the 200-year-old wine cellars to stables, ripping out the vineyards, and for the next 30 years bred some of South Africa’s finest racehorses. Milner’s grandmother, Lady Kate, was passionate about gardens and, together with three gardeners (one of whom still looks after the gardens today) completely redesigned and established the magnificent gardens I saw in May. Their son, Charles Milner, moved onto the stud farm to work with his father in the eighties, and Alex was born, grew up and has spent his whole life on Natte Valleij farm.

Heading through the gardens to the 200-year-old winery buildings

Three unlikely things would come together to result in what I think are some of the most trail-blazing, tantalising Cinsaults in the world: an obsession with cycling, a place steeped in history, and no money.

Milner was actually a super-league elite road-racing cyclist in his early twenties. His real plan was to make it to the professional cycling circuit in Europe. He kind of thought that winemaking, with its seasonal aspect, was ideally suited to give him time to ride his bike, which is all he really wanted to do – ‘a professional cyclist with a winemaking hobby’, as he describes it. That never happened. Instead, following in his eldest brother’s footsteps (Marcus Milner, winemaker at Warwick and now De Meye) he completed his degree in oenology and viticulture at Stellenbosch University and went to Provence to make wine at Domaine de Triennes. In 2005, due to changing fortunes in the horse-racing industry, Milner was able to move horses out and roll a couple of wine barrels in. Quite literally, a couple. There was no capital to bankroll a winery start-up, no family vineyards, and the winery wasn’t designed for wine – not any more, at least. Wine production started on a very (very) small scale.

It’s clear within minutes of talking to Milner that an awareness of history runs a continuous thread through everything he does. Perhaps it’s growing up on a 300-year-old wine farm. Perhaps it’s growing up with a long family history rich with English peerage. Although he never mentions his aristocratic roots (I had to do some serious research to find out that he’s connected to generations of earls, baronets and statesmen) and I suspect this may be because Milner has a very different outlook and values to those which shaped his colonial forebears.

Aside from his decidedly down-to-earth South African accent and casual and utter disregard for pretentiousness, there are other things that tell me this person is part of a changing South Africa. His joined-at-the-hip right-hand man at the winery is Kelvin Feku, a young Zimbabwean refugee who washed up at Natte Valleij by chance, desperate and working illegally for his cousin who was doing some building work for Milner. Within a year Feku was a cellarhand with papers and now, a few years later, he has a diploma in winemaking and is making his own remarkably good, delicious wines. Milner quietly paid for it all, while Feku achieved it all, and it’s clear to see the mutual respect, admiration and almost seamless thinking between the two of them as they walk us around the winery and through the tasting. Milner seeks Feku’s opinion throughout. It’s mentorship without glory or patronage. And, as I see it, it is another thread in Milner’s awareness of history – the impact our lives have had on others. The wall of Milner’s kitchen (in one of the houses on the farm which would have been an employee’s cottage at some point in the past) is engraved with ‘P.O.W. BT 27/12/1943’ by an Italian prisoner of war who was probably assigned to the farm to provide free labour. One of Milner’s wines, POW, is named after this unknown Italian prisoner.

Alex Milner and Kelvin Feku at the winery door (Brad Currin to the right!)

It was the history of Natte Valleij and its old winery that made Milner determined to make wine on the farm again. He can also talk for Africa (again, literally) about the history of Cinsault. The murmured rumour that lowly Cinsault, openly sneered at by the Cabernet growers of Stellenbosch, had been vitally important to the story of South African wine nagged at him. The reason, he contends, that there are these amazing pockets of old-vine Cinsault to be found in the Cape is because the co-operative winemakers needed Cinsault. They ‘smeared it all over the cellar … to lighten up a heavy Cabernet, to brighten up a flat Shiraz’, he tells Elizabeth Schneider in his interview on her Wine For Normal People podcast. But at the same time, Milner seems to balance his awareness of the past with a radical approach to cutting new ways and being different.

Alex Milner in his non-state-of-the-art cellar

The foot-pressing ‘lagare’ rudimentarily built during COVID lockdown in 2020 (the ‘ANNO 2020’ a wry nod to one of its long-retired predecessors – see below)

‘Anno 1913’ on one of the concrete fermentation tanks from the winery’s pre-stables days – they were all either removed or converted into storage rooms (and now toilets!) after the 1950s

For several years Milner made Merlot, Cab and other big, oaked reds in a cellar so rustic that it’s a wonder he still has all ten fingers, let alone bottled wine. But, he says, something didn’t feel right. He was thinking of getting a ‘proper job’. Cycling out to the family’s holiday home one day … Stop! Sorry. I’m going to back up here. Because here’s where the link between cycling, history and no-money-make-do comes in.

When Milner tells you he is a keen cyclist, take it with a cup of salt. In 2022, for fun, he cycled 837 km (520 miles) from Stellenbosch to his friend’s farm in Prieska, Northern Cape, on the Orange River. Before you even start to think about that, you need to know that he did this alone, without a support car, without a tent, on a gravel bike. And those 800-odd kilometres are through some of the most remote parts of South Africa. He slept wherever, along the way. Hung sweaty cycling gear on barbed-wire fences to dry. Ate dates to keep going. Until you’ve driven through hundreds of miles of rural southern Africa, it’s hard to image just how mentally, let alone physically, tough an undertaking like this is. Milner shrugs it off. The next year he cycled 752 km across the Karoo, again, by himself. Milner is not a ‘keen’ cyclist. I’m not even sure what the word is for his kind of cyclist. But it does give you some idea of just how focused, how minimalist, how down-to-the-bone Alex Milner is. It takes a certain kind of courage to face yourself and that level of physical and mental pain without respite or support, for hundreds of hours. It takes a certain kind of guts and also a wild recklessness, a thirst for life, to take risks like that. It takes a certain kind of monastic discipline.

Photo taken by Alex Milner during his cycle across the Karoo

So, back to that holiday home. Milner cycles 160 km (100 miles) to this very remote part of South Africa every time they go out there for a holiday – the rest of the family, sensibly, drives, bringing the provisions! On this day, halfway there, middle of rural nowhere, he gets a flat tyre. Curses. Stops. Sits on the side of the road in the dust and stones fixing the bike. Eats something. Notices he’s right by a vineyard. Hops the fence. Takes a look. Old bush vines. Cinsault. Definitely Cinsault. Chap ambles past, a labourer heading for the next farm. Tells Milner it’s ‘Hermitage’ – the old South African name for Cinsault. Milner tracks down the farmer. It’s Cinsault alright. Planted in 1978. The next year he buys the grapes and Natte Valleij’s first single-vineyard old-vine Cinsault is made, Wine of Origin Darling. After years of tasting the wine made from this very vineyard, I wrote, ‘Alex Milner's Cinsault Darling has always been my darling Cinsault’.

Now he makes wines, primarily Cinsault, from a jewelled collection of old vineyards in the Cape, all of which he has discovered on his bike. Riding a bike, he explains, is a very particular way to experience the environment. You get to know the wind – on which roads it’s in your face or behind your back, where it blows stronger. You get to know the pockets of places where the air is always colder or always hotter, and you get to see forgotten, hidden vineyards that you may not have seen from a car. This is how he finds his wines. Milner seeks out lost, forgotten, unloved, abandoned vineyards on his bike. The next generation of Milners, he tells me, can plant vineyards.

Alex Milner’s antique basket press which, until 2024, was man-powered to press every single kilogram of grapes that came into the Natte Valleij cellars

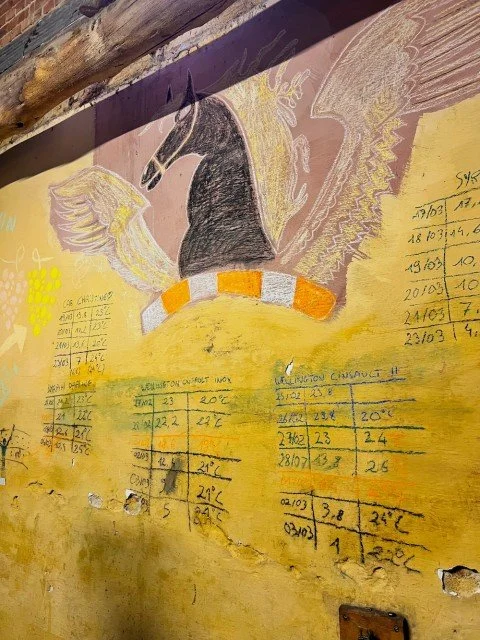

He still makes his wines in the most rudimentary way possible. Until vintage 2024, every single kilogram of grapes was pressed using an ancient basket press and sheer muscle power. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. Pressing grapes in that must be akin to medieval torture. During one particularly abundant harvest, Milner tells me, they were pressing around the clock, literally taking it in 24-hour shifts. Stamina? Bloody-mindedness? Luckily this is a man who can cycle 800 km through desert on his own. From foot-stomping grapes to harvest notes chalked up on the brick walls, the Natte Valleij winery is about as pre World War as it gets. UK Health & Safety inspectors would have a conniption. But, without a stash of cash, there is no state-of-the-art winery. So, you make do. You uncover the bones of a 200-year-old winery and use what’s there. You beg, borrow and recycle old equipment. I am quite sure that this make-do mentality, born partly of necessity, has played a huge part in informing the unplugged, stunningly pure profile of the wines Milner makes.

Record-keeping for 2025 vintage ferments (NB the horse, in recognition of the winery’s more recent past)